Danube Watch 3/2020 - Maps as Time-Machines

Maps as Time-Machines

We here at the ICPDR love maps. Maps provide an elevated level of understanding. They can make complicated data appear as clear to a layperson as it is to the expert who compiled the data in the first place. This is the reason why the ICPDR creates so many maps. Danube Watch has highlighted in recent issues the process, and great effort put therein, necessary to create the ICPDR's dozens of maps out of numerous datasets. Our own Zoran Major, Technical Expert for GIS and cartographer extraordinaire, explained the process expertly and with passion. (The article can be found in Danube Watch 1/2020, and is well worth the read!)

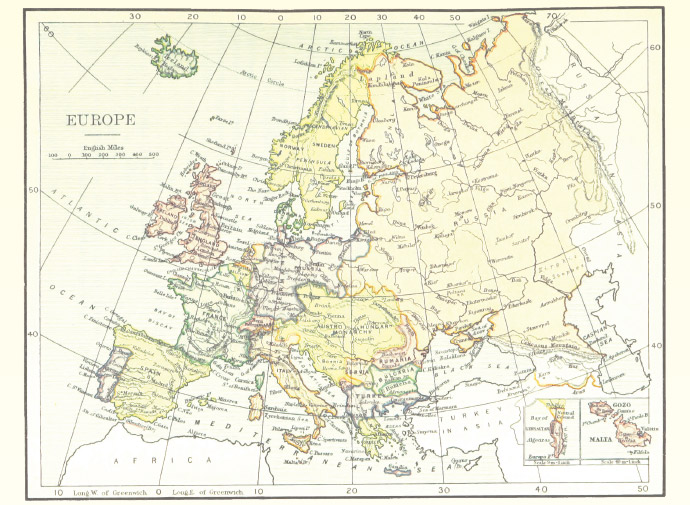

One of the most interesting ways that maps can help us understand the world around us is comparison. The ability to compare data that is reflected on what would otherwise be the same map is a valuable tool indeed. When it comes to the Danube River Basin, one could simply consult the vast array of ICPDR-created maps and have a wonderfully well-rounded idea of the many issues threatening the Basin, the ins and outs of the Basin's form and structure and many other aspects as well. To have a genuinely full conception of the Danube River Basin, however, requires the use of a time-machine, or the next best thing.

The past can be a tricky thing to conceptualise. Often, we can look around and see elements of our world, societies, cities and daily lives (just to touch on a few things) that are almost exactly as they were a hundred, two hundred years ago – or more. This is very true of many places within the Danube River Basin: from small villages to big cities. What can be difficult to imagine, however, is the ways in which the natural world around us changes, or, as is often the case, is changed.

In our most recent issue of Danube Watch, we highlighted a book by Gertrud Haidvogl, Wasser Stadt Wien: Eine Umweltgeschichte, which addresses the history of the Danube River and the numerous streams and creeks that defined and shaped the city of Vienna. The book also discusses the history of how and why these waterways changed, how the people living in the area changed them, in fact. The reasons are varied and many. What is important here is that these waterways are not the same waterways that shaped Vienna. This is also true of other parts of the Danube upstream and down, of the large tributary rivers and the small streams in the Basin. Maps greatly help the book highlight these dramatic shifts by allowing the reader to visualise the historic flow of Vienna's waterways.

For anyone with even a passing interest in the Waterways of the Danube River Basin, a bit of visual historical context can fill in information gaps or, at the very least, provide a fascinating glimpse into the way in which the region has changed over time. What areas had been wooded, which had been flood plains, which are now towns, cities, farmland, natural parks – this information does not need to be the stuff of idle pondering. Thanks to a uniquely interesting website, the past and the present can be compared directly.

Mapire.eu is a website consisting of digitalised historical maps from across Europe, but with a great focus on the Habsburg Empire and its successor states, digitally scanned and uploaded by the Budapest based Hungarian company Arcanum. The website has also been created with Gábor Timár, PhD as its scientific advisor and with the cooperation of many institutions including:

- The Austrian State Archives,

- The Hungarian National Archives,

- The Government Office of the Capital City Budapest,

- The Croatian State Archives,

- The Hungarian War Archives,

- The City Archives of Budapest and

- The Department of Geophysics and Space Science, Eötvös University.

With all of these resources put together in one place, the whole of the Danube River Basin can be better understood with the aid of historical context. This is due in no small part to Mapire's unique tools. Rather than simply presenting historical maps which have been painstakingly digitalised and uploaded, the website allows users to zoom in and out to see the most minute details contained within these maps.

This would all be wonderful enough, but Mapire takes everything a step further. Once users have chosen a particular historical map to pore over, an 18th century Austrian map of the imperial lands south of the Enns river, for example, they then have the ability to choose a 'base-level map' from either a current standard map or current satellite image map of the very same region. Then, using a slider-tool, the user can slide the image between 100% historical map view and 100% current map view, including any percentage in between, allowing the user to blend the maps together and really take in the dramatic changes and similarities that are revealed.

There are, of course, many other great tools users have access to. For example, users can also simply view the two maps side-by-side and synchronise them to scroll over the same areas at the same time. The site offers the ability to search for specific cities or regions easily, and also measure distances on whatever map is being viewed. Furthermore, some historical maps have even been digitalised in such a way as to allow them to be viewed in 3D, showcasing the geographical terrain and making the viewing experience feel all the more physical.

The process of achieving the quality digitalised versions of historical maps requires expertise and research. The first step when handling the old maps is 'geo-referencing'. The GPS coordinates for each pixel of the image, i.e. its position on Earth, must be determined. To do this, the methods used to create the original map must be determined along with the projections used and the projection parameters. This requires deep research and a great deal of practice. Serious manual work is required after the theoretical setup in order to perform the operation of geo-referencing properly. When this process has been carried out, the opportunity to view old maps together with current maps within a single system is possible.

The accuracy of the historical maps depends on the scale on the creation method of the original map. In the case of 1:2.880 scale cadastral maps from around 1850, the accuracy can reach up to 15 to 20 meters. During geo-referencing, maps of up to thousands of sections can be organised into a single image.

Top-end map scanners for large-scale, high-quality digitisation of large maps are utilised during this process. Thanks to their unique picture quality, very small texts on the old maps are also sharply displayed. With a gentle, precision roller mechanism, even the thinnest of documents is able to be scanned without damage. The scanning and lightning technology of these map scanners is designed to ensure that these old documents are not subjected to any harmful effects. The time under illumination is extremely short, thanks to the fast imaging sensors, which also prevents light-damage from harming the original maps.

For those who share the ICPDR's love of maps and the Danube, Mapire.eu offers an educational experience that will not disappoint. The only danger is the amount of time that someone can spend poring over the old maps, comparing them to maps of the regions today and deepening their knowledge of the lay of the land – so to speak. Go see what the Danube was and what it is, and then see where you end up.