Fighting for the sturgeons

Fighting for the sturgeons

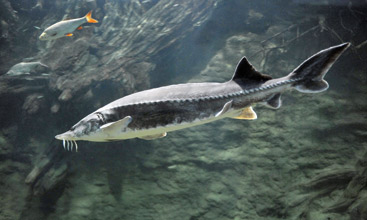

Once present in large numbers in the Danube River Basin, sturgeons today face threats from overfishing and illegal marketing, disruption of spawning migration, and habitat loss due to river engineering. Although they have outlived the dinosaurs, it’s not clear how much longer they can survive without urgent help.

From the six native Danube sturgeon species - some of which migrated as far as Regensburg on the Upper Danube - one is already extinct, one is functionally extinct, three are on the verge of extinction and one is considered threatened.

© Lubomir Hlasek

Sturgeons are a natural heritage of the Danube River Basin and a flagship species signalling the health of the habitats and ecosystems of the river and its tributaries. The dramatic decline of sturgeon populations in recent years has captured the attention of the Danube countries, and several projects across the basin are working to protect these ‘living fossils’.

Fighting overexploitation. Although most sturgeon caviar today comes from aquaculture facilities, caviar from poached sturgeon still finds its way to the market. A three-year project to fight sturgeon over-exploitation, jointly financed by the EU and WWF, has recently ended. Called ‘Joint actions to raise awareness on overexploitation of Danube sturgeons in Romania and Bulgaria’, the project worked with fishermen, law enforcement agencies and the aquaculture industry to reduce illegal fishing in those countries with the last viable populations of sturgeons in the Danube.

Thanks to the project, local sturgeon advocates in Bulgaria and Romania have raised the awareness of fishermen about sturgeon conservation and informed them about alternative sources of income. Project workshops for law enforcement authorities have helped add information and capacity to control illegal fishing, smuggling and trading, and plans are in the works to develop the first wildlife crime unit in Bulgaria. Furthermore, eight aquaculture farms in Bulgaria and Romania have committed to protect wild sturgeons beyond legal requirements. “The key to protecting sturgeons is to inform and train the central stakeholders,” says project leader Jutta Jahrl from WWF Austria.

A follow-up project has been submitted to expand sturgeon protection activities into Serbia and the Ukrainian Danube Delta. However, the current fishing ban in place in Bulgaria and Romania expires on 31 December 2015. With no defined protection measures by the governments beyond this, it is unclear how long the success of the project can last.

Protecting migration routes. One of the most significant – and literal – obstacles sturgeons must overcome is the Iron Gates Dams I and II, which interrupt their migration route. To gather dataabout how to operate effective fish passes so the dams could be reopened, a one-year preparatory project was conducted this year, funded by the European Investment Bank.

The project tested equipment to achieve the prevision required to track sturgeon positioning in relation to turbines at the Iron Gates Dam II. Results showed radio telemetry to be ineffective in the high radio noise environment, however new acoustic telemetry equipment allowed researchers to estimate the receiver’s distance from fish carrying the transmitter – impossible a year before – and project leaders in Romania held hands-on training in acoustic telemetry for teams from Bulgaria and Serbia.

As part of the project, a study compared genes of beluga sturgeons migrating to the Iron Gates with those spawning further downstream. Though researchers expected the two groups to differ, the genetic comparison showed that fish migrating to the Iron Gates are quite similar to the ones living and spawning farther downstream.

This project will form the basis for a three-year project, also to be funded by the European Investment Bank, to study the behaviour of sturgeons and other migratory fish at the Iron Gates dams and reservoirs.

A male beluga sturgeon is tagged at Dunavtsi, near Vidina, Bulgaria, as part of a project to track sturgeon positioning in relation to turbines at the Iron Gates Dam II..

Preserving genetic diversity. The Danube Sturgeon Task Force was established in 2012 to support the implementation of the Sturgeon 2020 programme. A new project, funded by the EU Strategy for the Danube Region’s START programme, is targeting one of the key topics of Sturgeon 2020: Ex-situ Survey to Preserve Sturgeon Genetic Diversity in the Middle and Lower Danube (Sturgene).

he Sturgene project will obtain an overview of existing facilities, broodstock and expertise and then develop a roadmap for ex-situ conservation in the Danube Basin, while mobilising further political and public support for sturgeon conservation. Measures will focus first on the Lower and Middle Danube, where wild migratory sturgeons still exist and Sturgene intends to secure their diversity and stem the decline in their population. However, the aim is to create facilities producing sturgeon fingerlings and supporting restocking programmes all along the Danube to reintroduce sturgeons in natural habitats and establish self-sustaining populations. A roadmap for the project, the first phase of which will run from 2016 to 2020, will be finalised in a few months.

However, the ex-situ conservation programme is not designed to function on its own. The programme will be effective only if accompanied by an extension of the current sturgeon fishing ban, a system of compensation for fishermen affected by the ban, enhanced cooperation with law enforcement organisations to reduce illegal fishing as well as a conservation programme to protect and restore natural habitats. All of these activities are vital to the success of the Sturgene project – and indeed to saving the sturgeons – and should be high priorities for governments in 2016.

Restoring natural populations. Restocking programmes have been largely unsuccessful at producing self-sustaining populations of wild sturgeons partly because fish born out of natural habitats do not ‘imprint’ on the river and are unable to use homing behaviour to locate spawning sites.

This challenge is being tackled by a new project, called ‘Restoration of sterlet populations in the Austrian Danube’ (LIFE-Sterlet). The project is organised by the Institute of Hydrobiology and Aquatic Ecosystem Management at the University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences (BOKU) of Vienna, with partners from the Viennese governmental body for river and waters (MA45 Wiener Gewässer) and the Institute of Zoology at the Slovak Academy of Sciences.

The LIFE-Sterlet project will create a genetic inventory of available brood stocks and establish a breeding container on the Danube Island in Vienna. Using water and sediments from the Danube, several hundred thousand eggs will be hatched each year and reared with natural food and exposure to predators.

Starting in 2017, the project will restock several thousand juveniles into three sites – the Morava River and the Wachau Valley and Donau-Auen National Park on the Austrian Danube – and specimens will be monitored by telemetry transmitters to gain a better understanding of habitat use. The project will run until 2021.